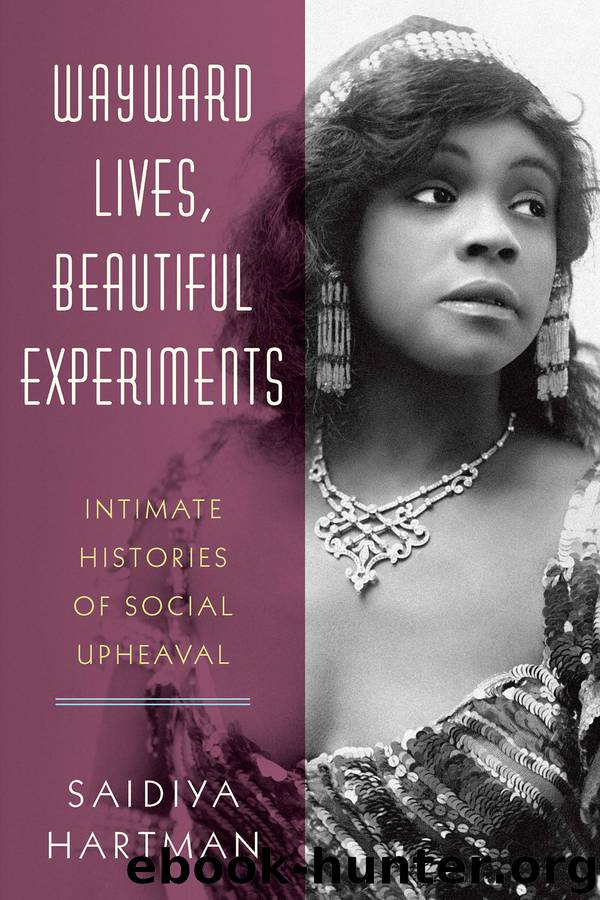

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by Saidiya Hartman

Author:Saidiya Hartman

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Epub3

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Until the night of July 17, 1917, Esther Brown had been lucky and eluded the police, although all the while she had been under their gaze. Harlem was swarming with vice investigators and undercover detectives and do-gooders who were all intent on keeping young black women off the streets, even if it meant arresting every last one of them. Being too loud or loitering in the hallway of your building or on the front stoop was a violation of the law; making a date with someone you met at the club, or arranging a casual hook up, or running the streets was prostitution. The mere willingness to have a good time with a stranger was sufficient evidence of wrongdoing. The court, like the police, discerned in this exercise of will “a struggle to transform one’s existence,” to stand against or defy the norms of social order, and anticipated that this non-compliance and disobedience easily yielded to crime. “The history of disobedience,” enacted in every gesture and claimed in the way Esther moved through the world, announced her willingness “to be ruined by standing against what is instituted as right by law.”

The only way to counter the presumption of criminality and establish innocence was to give a good account of oneself. Esther failed to do this, as did many young women who passed through the court. They failed to realize that the readiness or inclination to have a good time was evidence enough to find them guilty of prostitution. It didn’t matter that Esther had not solicited Krause or asked for or accepted any money. She assumed she was innocent, but the Women’s Court found otherwise. Esther’s inability to give an account that would justify and explain how she lived, or atone for her failures and deviations, was among the offenses levied against her. She readily admitted that she hated to work, not bothering to distinguish between the conditions of work available to her and some ideal of work that she and none she knew had ever experienced. She was convicted because she was unemployed and “leading the life of a prostitute.” One could lead the life of a prostitute without actually being one.

With no proof of employment, Esther was indicted for vagrancy under the Tenement House Law. Vagrancy was an expansive and virtually all-encompassing category; like the manner of walking in Ferguson, it was a ubiquitous charge that made it easy for the police to arrest and prosecute young women with no evidence of crime or act of lawbreaking. In the 1910s and 1920s, vagrancy statutes were used primarily to target young women for prostitution. To be charged was to be sentenced because nearly 80 percent of those who appeared before the magistrate judge were sentenced to serve time; some years the rate of conviction was as high as 89 percent. It didn’t matter if it was your first encounter with the law. Vagrancy statutes and the Tenement House Law made young black women vulnerable to arrest. What mattered was

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American Studies | Asian American Studies |

| Disabled | Ethnic Studies |

| Hispanic American Studies | LGBT |

| Minority Studies | Native American Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32554)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31951)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31935)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31922)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19040)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15976)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14494)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14062)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13967)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13357)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13356)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13236)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9329)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9283)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7500)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7309)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6748)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6617)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6270)